Abstract

This research aimed to develop a framework for Crisis on Discernment of Vocation (CDV). The research approach is qualitative and the design is Grounded Theory. The selections of the study are eighteen college and eighteen theological seminarians who come from five different seminaries. Semi-structured interview is used to gather the data. The results showed five different crises namely: crisis on relationship, health and death in the family, identity crisis, sexual abuse and crisis on academic formation. There are sub-crises in each crisis. These crises happen within the seminarians’ being as they undergo seminary formation inside the seminary. There are stages of the crisis on discernment of vocation. First stage is the origin of their crisis which is their family. The second stage is the beginning of their vocation and greater exposure to the Catholic Church and the last stage is when they are in the college and theological seminaries experiencing the five different crises. As a natural reaction to their crises, seminarians develop coping mechanisms. They pray at the chapel which is their place of refuge. The seminarians reach out to their fellow seminarians to release the tension caused by their crisis, and they also seek professional help like consulting clinical psychologist and spiritual directors inside the seminary. Equally important as coping with the crises, are the interior dispositions of seminarians. The seminarians have positive assessments in relation to their crises.

Keywords: Crisis, Discernment of vocation, Priestly vocation, Seminary formation

Introduction

The Philippines is a predominantly Catholic country in Southeast Asia, now celebrating its 500 years of Christianity. Since the first missionaries set foot on the Philippine islands, the Catholic Church has produced from among the Filipinos a significant number of indigenous priests, bishops, archbishops and cardinals. It has founded many houses of formation: minor seminary, college seminary and theologate. It has also sent missionaries abroad, which is a sign that the Catholic Church here in the Philippines is vibrant and that Catholicism is the predominant religion of the archipelago (Cornelio, 2018).

Be that as it may, the Philippine Catholic church is composed of lights and shadows. The light may be that it has been gifted with faith and it has flourished. One of the shadows is the sad decrease of priestly vocations. According to Marshall (2018) and Glatz (2019), the number of major seminarians all over the world in the year 2011 was 120,616. In the next four years, there were steady decreasing numbers of priestly vocation. The last data provided by Agenzia Fidez (2018) show that in the year 2017, there were only 115,328 major seminarians worldwide. And so, in the universal Catholic Church, vocation to the priesthood is dwindling in number. There are many reasons for this alarming decline of vocation. It can be an experience, an occurrence that transpires among the seminarians inside the seminary. This research attempts to discover the processes that are within the being of seminarians and are happening inside the seminary while they are under formation and it is crisis in the discernment of vocation. This is the phenomenon that is being considered, and this research traverses on its framework.

To properly understand the crisis in discernment of vocation, it is important to comprehend priestly/seminary formation, for this is the setting where the research was conducted. A priest is a product of seminary formation. In the Philippine context, seminary formation starts as early as high school level, in the minor seminary (Cruz, 2012). Today, minor seminaries provide a residence for six years because two years of senior high school are included in the minor seminary set up. The college level is the next and seminary training lasts for four years. The last level of seminary training is the theologate which normally lasts for five years including one year for spiritual formation. The church believes that priestly vocation arises in various circumstances and at different stages of human life as early as childhood, adolescence and in adulthood (Pope Francis, 2016). This means that a seminarian can enter in the minor seminary or if not, in college and in extraordinary circumstances, directly into the theologate. There are four areas of priestly training namely: spiritual, pastoral, academic and human formation (Pope John Paul II, 1992). The seminarians have a prayer life (celebrate the Eucharist, go to confession, pray the Liturgy of the Hours, have devotions, etc.), which is part of spiritual formation. The spiritual director is the facilitator of spiritual formation. For their pastoral formation, seminarians have apostolate areas; they go to the barrios to be immersed in the lives of people, conduct seminars and give recollections, and participate in other activities such as prison, hospital, and catechetical apostolates. The pastoral director is the facilitator of pastoral formation. For their academic formation, the theologate offers pastoral and theological degrees, and the college seminary provides a degree of Bachelor of Philosophy. The seminary is an academic institution. The one in charge of academic formation is the dean of studies. They have a schedule for the whole day, and included in this are times also where they can play, sleep, and eat just like normal human beings. Together with the priests who are in charge of their formation, – the seminarians have community life, socialization hours, picnics, and go out every week to buy their basic necessities. This is part of their human formation. The human formation is directed by the prefect of discipline. The overall program director of the seminary is the rector.

Constructs in this research: crisis, discernment, and vocation

Crisis is a psychological concept that is central to this research. There are seven characteristics of crisis. 1) Crisis has precipitating events (Public Health Nigeria, 2020). This refers to predictable events such as getting ordained, scrutiny, moving to another level of seminary training, etc. This can also be unpredictable such as the experience of a sudden death of a parent, disasters, etc., which can be an internal or an external occurrence. 2) Crisis is time limited. This means the duration is either six to eight weeks, or it can be shorter or longer depending on the type of and intensity of the crisis (Jackson-Cherry & Erford, 2018). However, the crisis’ impact may last a lifetime (James & Gilliland, 2017). 3) Crisis creates a state of imbalance and disorganization on the person (Cherry, 2020; Hunter & Ramsey, 2005). The crisis creates disequilibrium that disturbs the normal functioning of the individual (Caviola & Colford, 2018). 4) Crisis is about perception. It causes the person to use his cognitive interpretation or appraisal, and this accounts for the truth that everyone assesses the crisis in varied ways. Crisis is universal since nobody is exempted from breakdown, and it is also idiosyncratic because one may overcome a crisis while others cannot (James & Gilliland, 2017). For example, when a seminarian is kicked out from the seminary, it can be the end of the world for him while for another seminarian, it may be a chance to get some time off, rest and get a new satisfying life outside the seminary, especially when he has been in the seminary for a long time. 5) Crisis breaks down one’s ability to cope (Caviola & Colford, 2018). The goal of crisis intervention is to restore stability or balance (Leeming, 2020). The professional helper has to tap the reservoir of resiliency of persons in crisis, their support system, and their coping mechanism so that they can overcome crisis (James, & Gilliland, 2017). 6) Crisis is both a danger and opportunity. The Chinese have defined crisis as 危機 wei chi, time of danger and opportunity (James & Gilliland, 2017). One seminarian felt that the separation of his parents had a devastating and frustrating impact and there was no meaning of life while another seminarian perceived the separation of his parents as occasions of realization of his inner strength. In the occasion where a parent of a seminarian dies, interpersonal relationships are strengthened because there is assistance coming from different seminarians and the whole community of the seminary and parish; thus, this crisis can bring out the best in others. There are those who remain in “danger” after the crisis because it is so overwhelming that it leaves grave pathological disorders such as suicide, Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), anxiety, etc. (James & Gilliland, 2017). 7) There is a necessity of choice in a crisis. The English etymology of the word crisis is the Greek term “krinein” which means “to decide” (Caviola & Colford, 2018) highlighting that crisis is a moment for decision making. It must be noted that the decisions can either have positive or negative outcomes (Jackson-Cherry & Erford, 2018). In summary, crisis is an intolerable situation or devastating event that immobilizes a seminarian, preventing him from functioning normally, and it results in disorganization, and disequilibrium. It can either be expected or unexpected. In unexpected crisis, normally, people are not prepared or they do not know how to respond to a crisis situation or event, and there are feelings of fear, shock, anxiety, guilt, and grief that surfaces (James & Gilliland, 2017). For this research “crisis” is the turning points or significant stages, situations, and events that have great impacts on the vocation and life of a seminarian while they are in seminary formation. It may have a negative impact when not resolved or it may be a possible source of growth when understood, identified, resolved, and integrated into the life of a seminarian.

In this present era, many believe that God continues to call people to have a mission in life. The personal call of God, which is the concern of this study is the priestly vocation. God does not directly and personally call persons for the priestly vocation. There is an element to be considered here which is called “discernment.” This is the process of determining cognitively or employing judgment in identifying God’s desire in one’s life or his divine plan for a person’s life. Discernment is a decision process that a seminarian undergoes confronting a course of life he undertakes. It is both spiritual and psychological in nature (Knapick & Kosturkova, 2018). The spiritual aspect of discernment is trying to understand the will (or the plan) of God for one’s life. Discernment, when related to priestly vocation, must consider intellectual ability, leadership qualities, and a life of calling for lifetime humility, moral integrity, utter self-oblation, and genuine faith experience. The psychological aspect of discernment is the search for meaning and purpose of life (Tillich, 2008; Frankle, 2006). Discernment of vocation occurs before a candidate enters the seminary. This is just one aspect of discernment of vocation. It continues when the candidate is accepted as a seminarian. The discernment of vocation that is the subject of this research is what happens during seminary formation while the seminarians are inside the seminary. In reality, the whole seminary formation is a deeper and greater discernment of vocation (Keating, 2019; Dolejsi, 2016). Some of the discernment questions that seminarians usually ask are: Am I called by God? Am I worthy of the priesthood? If I am really called to the priesthood, how come I am experiencing this and that crisis? My family is in a difficult situation. Is the Lord asking me to deal with my family first before I become a priest? Will the Lord permit me to leave the seminary? What is the Lord asking me to do in this situation? What is God’s real plan for me? There are many other discernment questions that seminarians encounter as they proceed to the ladder of formation. To sum up, discernment is the process of understanding and interpreting a seminarian’s state or experience in relation to his vocation to the priesthood and life in the seminary. It deals with basic questions about the priesthood, vocation, ordination, etc., and makes the seminarian reflect, perceive, grasp, and comprehend something obscure and in the course involves decision and judgment (Leeming, 2020; Hunter & Ramsey, 2005). In this research, discernment is the process of reflection and introspection, and the seminarians employ their cognitive faculty and emotions are triggered and lead to decision making. The decision in discernment of vocation affects the present and the future course of the life of a seminarian. It also touches on the seminarians’ interpersonal relationship, such as their relationship with the formators, bishop, priests, family members, and other people such as parishioners, and benefactors. The discernment is both spiritual and psychological.

The third construct in this study is vocation. Vocation here is not a career but a calling (Leeming, 2020). Davie et al., (2016) presented a theory of vocation and there are three essential elements of this. First element is the universal call to holiness as stated in the Dogmatic Constitution on the Church “Therefore in the Church, everyone whether belonging to the hierarchy, or being cared for by it, is called to holiness, according to the saying of the Apostle: For this is the will of God, your sanctification” (Flannery, 2014). The universal will of God for all to be holy is an essential characteristic of human life. This universal call to holiness presupposes a personal God who actively calls or invites men and women to commit themselves to Jesus in a unique way. This started at baptism. Now there is a call to personal vocation to grow in holiness which is perfection (Davie et al., 2016; Hunter & Ramsey, 2005). The second element of the theory on vocation is the specific Christian vocation to priestly and religious life. The vocation to priesthood demands a distinctive personal and intimate relationship with Jesus as a shepherd and sheep, vine and the branches, master and servant, the caller and those who are called. It would be a futility and falsity to remove Jesus from the priesthood (Cruz, 2012). The third element of the theory on vocation is the church role in the discernment of vocation. In discernment of vocation, the church fosters, safeguards, esteems and must love vocation (John Paul II, 1992). Pope Francis (2016) also said, “It means guarding and fostering vocations, that they may bear mature fruit. They are uncut diamonds, to be formed both patiently and carefully, respecting the conscience of the individuals, so that they may shine among the People of God.”

There are three church authorities that are duty bound in accompanying the seminarians in their discernment of vocation while they are undergoing seminary formation. Canon Law #239, Section one states, “In every seminary there is to be at least one spiritual director, though the students are also free to approach other priests who have been deputed to this work by the bishop” (Corriden, 2019). Pope Francis (2016) speaks of the journey of formations, so the specific person who is considered official “co-journeyer” in the discernment of vocation is the spiritual director of the seminary. The second church official that acts in discernment of vocation is the bishop. The bishop becomes the legitimate ecclesiastical authority in the discernment of vocation [especially during ordination] who examines or investigates the candidate before ordination (Davie et al., 2016; Cruz, 2012). The third authority that accompanies the seminarians in their discernment of vocation are the priest-formators or seminary formators. The seminary formators help prominently in the discernment of vocation (Pope Francis, 2016). They are in charge of the sufficient education, formation in the community life, growth in pastoral charity, and the spiritual and human formation of the seminarians (Pope Francis, 2016; Pope John Paul II, 1992). Every year, they scrutinize the seminarians and present to the bishop an evaluation of each candidate.

Crisis on Discernment of Vocation (CDV)

The research defines crisis in discernment of vocation as the period or turning point in the life of seminarians characterized by increased tension disturbing the normal life of candidates to the priesthood and their environment. It causes the seminarians to think, judge, and decide, making them grow and mature. When crises on discernment of vocation are not resolved, they may cause pathological disorders or become reasons for seminarians to leave the seminary. When unresolved crises are buried in the seminarians’ life, they recur in another time and occasion and explode causing greater damage in priestly life (Fernandez, 2001; James & Gilliland, 2017).

“Crisis in discernment of vocation” is the situation, event, or the turning point in the life of seminarians where they experience tremors in life because their normal understanding is not enough anymore to meet the crisis. The seminarians’ emotional, cognitive, and normal faculties during crises of discernment of vocation are in a state of imbalance and disorganization. The CDV does not happen one time. It is a long process, so there are stages and they are both spiritual and psychological. In the stages of the crisis of discernment of vocation, the seminarians need professional help and accompaniment which involves the decision-making process.

Theories to Explain CDV

This research chooses two theories to explain CDV and these are: 1) the Psychosocial Theory of Erikson, and 2) Denzin’s Theory of Epiphanies. Erikson (1993) was the psychologist who theorized on lifespan development. In summary, the first stage of development is infancy (from birth to one year old), and the psychosocial crisis in trust versus mistrust. The next stage is early childhood (from one to two years old), and the psychosocial crisis is autonomy versus shame and doubt. The third stage is preschool (from three to five years old), and the psychosocial crisis is initiative versus guilt. The fourth stage of development is school age (from six to eleven years old), and the psychosocial crisis is industry versus inferiority. The fifth stage of development is adolescence (from twelve to seventeen years old), and the psychosocial crisis is identity versus role confusion. The sixth stage of development is young adulthood (from eighteen to thirty-four years old), and the psychosocial crisis is intimacy versus isolation. The second to the last stage of development is adulthood (thirty-five to sixty years old), and the psychosocial crisis is generativity versus stagnation. The last stage of development is old age (from sixty-five years and above), and the psychosocial crisis is ego integration or despair.

The development of a person follows a path called epigenetic development, which means that each stage develops at its proper time and one stage emerges from and is built upon a previous stage (Feist, et al., 2018). Erikson (1994) explained the epigenetic principle by claiming that “anything that grows has a ground plan and that out of its ground plan the parts arise, each part having its time of special ascendency, until all parts have arisen to form a functioning whole” (p.92). Also, each stage in the lifespan is an interaction of opposites (sometimes it is also called developmental tasks), or sometimes this is viewed as a “conflict” or “psychological crisis” (Carver & Scheier, 2016). The idea of “conflict” or “crisis” here are switchable.

For the purposes of this research, the writer used the word crisis as a “turning point,” which means that a state when potential for growth is high but the person is also quite vulnerable. The crisis is a struggle of attaining a psychological quality or failing to achieve it (Carver & Scheier, 2016). The developmental task (psychosocial conflict) needs to be resolved by the person in order to move onto the next stages (James, & Gilliland, 2017). However, there can be multiplicity of conflicts because an earlier stage or other stages were not resolved. These are sometimes called “excess baggage” which in Latin is “impedimentum” (James, & Gilliland, 2017).

The seminarians involved in this study belong to two stages of development, namely: adolescence (12-17 years old) and young adulthood (18-34 years old). The age ranges provided by Erikson are approximations.

One of the crises the seminarians are facing is identity crisis against role confusion. One of the critical developmental stages is adolescence because a person must come out with an ego identity (Feist, et. al., 2018). Identity emerges from two sources: 1) consolidation of self-concepts from previous stages (like childhood, play age, school age self-concept) and 2) integration of the view of the self with historical and sociological context, which means conformity with a standard (Feist, et al., 2018). The identity of seminarians is something developed in a consensus with the people they have been dealing with, such as priests, fellow seminarians and other significant others. Identity then is the blending of a personal concept (private) and a social concept (public) (Carver & Scheier, 2016). If a person is unable to form a self-identity, then one undergoes role confusion which is a result of repudiating parents’ value, peers’ standards, and community standards. This is the absence of direction in the sense of self.

Young adulthood is also the developmental stage of the theologians. Their challenge is intimacy versus isolation. Intimacy is a close warm relationship with someone with readiness to commit oneself to that someone (Feist, et al., 2018). It is the ability to fuse one’s identity with someone’s identity without losing his. Thus, this developmental stage requires solid self-identity in the previous stage. This intimate relationship is caring, and the person is willing to share the most personal matters of oneself with the other and in return must be willing to accept others’. The commitment is with the readiness to sacrifice, which is the moral strength of living up to that commitment (Carver & Scheier, 2016). Isolation on the other hand is feeling separated from others due to incapacity to take risks in a relationship and inability to make commitment. It can be that the other does not feel that someone does not fill his/her own needs. If a person withdraws into isolation because he does not recognize the other as equal, he can become self-absorbed that in the future cannot establish a relationship (Carver & Scheier, 2016).

The second theory that is related to the crisis on discernment of vocation is the theory of “epiphanies.” Denzin (2003) believes that there are events in the life of a person that have great impacts. These can be “turning points,” which may change the life of an individual.According to Denzin (2003), there are four major types of epiphanies:

- Major epiphany–those moments that touch the very fabric of a person’s life. Their effects are instantaneous and long term.

- Cumulative epiphany–those epiphanies that signify occurrences, or reactions, to events that have been going on for an extended period but become “last straw” that prompts a change (Griffiths, et al., 2016)

- Illuminative or minor epiphany–those events that are minor yet characteristically illustrative of major problematic moments in a relationship.

- Relived epiphany–those occurrences whose effects are instant, but their meanings are only specified later, in remembrance, and in the recalling of the episodes.

These four types of epiphanies may build upon one another (Denzin, 2003). A crisis on discernment of vocation among seminarians may be first interpreted as a major, then minor, and then later relived epiphany. A cumulative epiphany will later explode into a major epiphany (Fernandez, 2001).

Research Methods

The research approach is qualitative, and the design is Grounded Theory. The crisis on discernment of vocation of seminarians under formation is the focus of the study. According to Tie, et al. (2019), Grounded Theory as a research design sets out to collect data and then methodically develops and discovers a theory derived directly from the data. It is distinguished from other qualitative methods because its goal is to generate theory from data. Grounded Theory data analysis manages word, language, meanings seeking to organize and reduce the data gathered into themes, which in turn can lead into framework and theories (Tie, et al., 2019). Grounded Theory aims to produce a theory accurately representing the real world of the seminarians in college seminary and theological seminary and hopes to seek fresh and new findings that are practical and simply based on the experiences of selected seminarians. The basic research question is what framework can be explored on the crisis on discernment of vocation among selected seminarians. The primary aim of the study is to understand the crisis of discernment of vocation the seminarians experience while undergoing formation inside the seminary.

Selection of the Study

Inclusion Criteria

Those who are involved in the research are eighteen college seminarians, who belong to three college seminaries and are studying philosophy. These seminarians have been inside the seminary for more than one and a half years, excluding their stay in the minor seminary, if they did. Other participants are the eighteen theological seminarians, fourth and fifth year theology who belong to two theological seminaries, regional and archdiocesan theological seminaries. They underwent college seminary formation for four years and have resided and undergone theological studies for four years, too. This means that they have been residing inside the seminary for at least eight years excluding their stay in the minor or high school seminary. These five seminaries are from Northern Luzon.

Exclusion Criteria

Those who are not included in the study are seminarians (1) who are in regency program; (2) who are in the religious order or religious congregations such as Jesuits, Dominicans, Franciscans, Benedictines, etc.; (3) who are on leave of absence; (4) who are already done with their seminary formation waiting to be ordained [or on pastoral program]; (5) who are expelled from the seminary [kicked out]; (6) minor or high school seminarians.

Data Explicitation

This research employed qualitative interviewing which is semi-structured interview as a technique of collecting data by face-to-face conversation with the seminarians. The main goal of this technique of data gathering is to find out about the seminarians’ experiences, thoughts, feelings, values, and beliefs (Bryant, 2017). When travel was restricted due to the COVID 19 protocols, the border personnel required quarantine days, swab tests, and other difficult requirements for travelling, so online semi-structured interviews were then employed. The semi structured interview lasted about 45 minutes to 1 hour for every seminarian.

The researcher first used open/substantive coding which is the first step of analysing data in Grounded Theory. Substantive coding is bottom-up coding (Psaroudakis, et al., 2021). Since there were thirty-six selections, there were thirty six rows and several columns for their responses. There was more data given by the theologians than the college seminarians, so more columns were used in the substantive coding among theologians. The researcher began to segment or divide the data into similar groupings and formed preliminary categories of information (Flynn & Korcuska, 2018) about the experience of the seminarians. Substantive coding is sometimes also called open coding. In the substantive coding, it is helpful to keep the codes in the language or meaning that the participants used (O’ Connor, et al., 2018).

Axial coding was the next step. Concepts are collections of codes of similar content, and they group data together (Flynn & Korcuska, 2018). Then the researcher began to identify together the codes into groupings, distinguishing them from others. These are concepts being marked (Tie, et al., 2019) to avoid confusion. The third step was selective coding. Categories are similar concepts abstracted (Flynn & Korcuska, 2018). Most of the time, the concepts are from detailed, similar, local information to abstract categories. The last coding was theoretical coding. It is weaving the fractured categories together (Tie, et al., 2019) to come up with themes and subthemes. In this data explication, there were displays of the data then reduction of the data to better understand the experiences of the seminarians on crisis on discernment of vocation. Constant comparison was also used, assuring that all the data are systematically compared to all other data and this is for the purposes of data reduction.

From this point on, in the findings and discussions, direct quotations from the interview are distinguished using italics. The quotation from college seminarians is identified by the abbreviation CS with corresponding number while the quotation from the theological seminarians is identified by the abbreviation TS with corresponding number. The participants’ words are very important for they describe the seminarians’ experiences, thoughts, feelings, values, and beliefs, which are related to the lived experience of crisis on discernment of vocation.

Findings and discussion

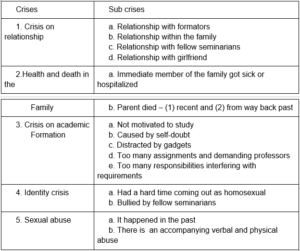

1. The Five Crises and Sub Crises

The most common crisis of seminarians that shook their discernment of vocation is crisis on relationship. Most of the seminarians were experiencing a crisis in their relationship within the family. The crises in relationship within the family are: a father wanted a nursing college course for his son, a father also wanted his son to become a military man and in another seminarian it is the grandfather who wanted his grandson to be a nurse just like his other grandsons. These parents and grandparent did not support the vocation of their son. Also a mother of a seminarian decided that his son is not joining the thirty-day retreat which is a conclusion of the theological formation and prerequisite for ordination. Two fathers physically and verbally abused their son at a young age and now it has psychological effects on their sons. A seminarian had difficulty relating with her sister who is working abroad and she is the one supporting him financially in his seminary financial obligation. In one seminarian, his father and mother almost broke up because of the family business that went almost bankrupt. In another case, a father left the family and had another family and in another case it was the mother who left the family and after five years had another family.

One seminarian experienced his parents’ separation when he was in grade five. In the interview, TS18 uttered, “My parent’s separation was very painful. I cried for many hours while they were shouting and fighting. I did not matter to them. They wanted to be separated.” He recounted how he lived with his grandparents and was sad for many days. One seminarian had a strict father. He is the only son in the family yet the father encouraged him to enter the seminary. Later, this seminarian found out that his father had a relationship with a best friend of his. TS12 said, “I was very angry with my father. My world was in chaos; I went to drink alcohol and I did not listen to anybody who was saying something to me. I was hurt and I rebelled against my father.” Later on, while in formation, the seminarian realized that he became irritable with formators and accepted the possibility that his anger with his father was transferred to his formators.

There is research by Alink et al., (2019) on the effects of dysfunctional parents. The research mentioned several effects on children of dysfunctional parents such as intergenerational transmission of maltreatment, and development of psychopathology such as depression and posttraumatic disorder. Allen (2018) described that dysfunctional parents can be demanding, over critical, perfectionists, and narcissistic. Nusinovici, et al., (2018) tells us of multiple negative effects of parents’ separation on children, such as blaming themselves, being stressed and damaging effects on motivation and learning-related behavior.

Relationship with formator is another sub crisis of seminarians on relationship. One seminarian had a crisis on relationship with his prefect. His prefect confronted him for returning to the seminary late. This happened because they visited a sick seminarian in the hospital. The seminarians who went to the hospital got lost in the hospital and they returned late that was almost midnight. The prefect got mad at them and told them that the seminarians can be kicked out for this indiscretion. CS2 said, “I hate him because he was very materialistic (with so many gadgets), and very authoritative. He is a hypocrite in telling us to have simple life style yet he has many accessories.”

Weigel (2019) wrote an article about American priests, bishops, and cardinals who were put in a bad light by the media. But American seminarians did not leave the seminary as they know very well these crises that afflicted the Catholic Church in America. As a response to the crisis, the seminarians prayed, had fraternal solidarity, and had a deeper sense of commitment to the Catholic faith.

Relationship is an essential part of seminary life, which is lived in a community. Seminarians come from different family backgrounds, sometimes of different cultures, languages, ways of life and physical attributes. Differences make community life lively. When everyone is the same community life becomes dull. In this research some seminarians are older; in the college seminary the average age of participants is 20 years old but one seminarian is 26 years old. In the theological seminary, the average age of participants is 26 years old; one seminarian is 38 years old. Because of age gap, cognitive maturity, experiences in life, one feels a stranger. CS16 stated, “I could not relate with them because I am older than them. I feel like I am an outsider. They see me as mature, and I perceive them as young.”

Knapick and Kustorcova (2018) in their research speak of younger seminarians having a crisis because of disappointments on the faults of their older brother seminarians.

Another crisis in the relationship that seminarians experienced was with their girlfriend. Celibacy has a long history in the Catholic Church. Some theologians have argued that historically it is not an essential part of the priesthood of Jesus Christ (Daly, 2019) while other theologians asserted that it is a substantial part of the priesthood (Bugnolo, 2020). In this research, TS15 had a girlfriend when he was not still a seminarian. Now he has another girlfriend and he said, “We did not have a closure of our relationship and ordination is fast approaching. I am pressured and I am in a crisis.”

The study made by Knapick & Kosturkova (2018) on seminarians tells us that one of the major crises of seminarians is the crisis on celibacy. Dolesji, (2016) stated that discernment of vocation happened inside the seminary while the seminarians were being formed. However, there is an end to discernment when it comes to celibacy. Keating (2019) stated that celibacy is an intense discernment where seminarians are seized by the Divine Beauty.

Another most common crisis of seminarians that affected their discernment of vocation is death in the family. Death is a natural part of life. Death nevertheless comes as a surprise to people. The mother of a seminarian died in a car accident. The last visit and encounter of the mother and seminarian became very memorable. The seminarian did not expect his mother to visit him at that time, so he went out to buy things he needed in the seminary and was not mindful of time. Upon returning to the seminary, his mother had been waiting for a long time. The mother gave a sermon and the seminarian was apologetic. TS17 expressed, “I miss her a lot and how I wish her to be there when I will be ordained.” That was his last memory of his mother.

Also, one parent died recently (2020). The health protocols became a hindrance for the seminarian to be connected to his father who was dying of cancer in Manila. CS8 said, “I was very frustrated with the difficulty imposed by the pandemic on suffering people like me. I had trouble getting to Manila and going to the hospital where my father was dying. I had to content myself with a video call.” Later after the burial, during the interview, he was saying, “I was frustrated with God and with myself. Sometimes I do not know what to feel. Sometimes I do not like to feel.”

The research of Long et al. (2018) suggested that significant family members should be involved during the last hours of the patient. It is important to put closure to the relationship with a father or mother. The situation created by the pandemic created extensive changes in saying goodbye to family members.

Another most common crisis of seminarians that affected their discernment of vocation is health in the family. Eastern culture treasures their family. Filipino seminarians give importance to family. One seminarian had an urgent telephone call that his brother was in the hospital. He did not go home but asked his other brother to go directly to the hospital. In the video call, TS14 was so surprised because his brother was so thin. “I was worried that he might die suddenly, looking at how unhealthy he was.” His brother used to be the healthiest among the siblings. He was also shocked that there is no permanent diagnosis in the medical record of his brother. Only to find out that his brother’s wife was having illicit affairs.

Thompson and Parsloe (2019) made a study about how family members explore the complexity trying to understand the health issues of their family members. Sometimes family members are frustrated, helpless, sad, and resigned when confronted with illness in the family, but they desire for more information and answers to uncertainties.

A different crisis that disturbed the seminarians’ discernment of vocation is academic formation. Some of the seminarians had doubts about their intellectual capacity. TS1 and TS5 said “My classmates are better off than me.” Another seminarian was not motivated to study and is distracted by modern gadgets. CS1, CS4 and CS5 said. “There were too many assignments at the same time and professors were too demanding.” Some believed that their responsibility in the seminary community interferes with their time of fulfilling their academic requirements.

Adubale and Aluede (2017) made a research on Catholic Major Seminaries in Nigeria regarding their counseling needs. The main counseling need of major seminarians in Nigeria is academic needs. Seminarians struggle to meet the academic demand of the intellectual formation of the seminary (Adubale & Aluede, 2017).

Another crisis that seminarians experienced in the seminary is identity crisis. The seminarians who are having identity crises have not come out with ego identity which would emerge from consolidated self-concept and integration of how he views himself from historical and sociological context (Carver & Scheier, 2016). The identity of a seminarian is a blending of personal concept of himself and social concept which clearly the identity of seminarian as the church teaches. He is in the seminary and being formed as a priest (Cruz, 2012). One seminarian is effeminate and has tendency of attraction to the opposite sex. TS11 said, “I had a hard time coming out as a homosexual. My parents did not know about it.” CS6 said, “I was bullied by other seminarian because I am a homosexual.” They believed that I am out of place because this is a sacred vocation for males. The identity of these seminarians remains strictly a guarded secret. Caution and secrecy make them alone with themselves. When they are with other seminarians they have to wear a mask of normal male behavior.

Prusack et al., (2021) made a study on Polish seminarians and according to this research, those seminarians who have a sense of personal identity, individuality, self-fulfilment and freedom can decide and have personal responsibility. The study of Prusack et al. (2021), indicated that seminarians’ decision to enter the seminary understood the specific values, and lifestyle of the seminary as a formation house of candidates to the priesthood. The seminarians have a sense of being the right person in the right place. Living with a community of seminarians, a seminarian can experience a sense of acceptance and self-worth which helps him establish self-identity.

The last crisis that affected the seminarians’ discernment of vocation is sexual abuse. Sex used to be a taboo topic in the seminary and the Catholic Church. This forbidden subject is essentially related to the vow of celibacy. The vow of celibacy is not a denial or repression of sexuality (Cruz, 2012). TS8, one of the selected seminarians in this study bravely spoke of the experience of his sexually abusive fellow seminarian, “I was angry with God and asked Him why He has given me this pain and suffering. I chose Him and I entered the seminary. How can this happen to me?” The crisis this seminarian experienced was traumatic and the immediate effect on him is the inability to trust. This is due to the reality that the abuser was still present (his contemporary) during college years.

Cavadini et al., (2018) made a research on seminarians in the USA. The study tells that ten per cent of US seminarians have experienced sexual harassment, abuse or misconduct.

Table 1. Five different crises and sub crises that seminarians experienced that affected their discernment of vocation

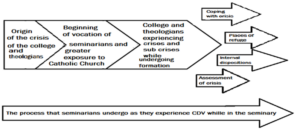

2. Framework of Crisis on Discernment of Vocation (CDV)

Tie, et al., (2019) in their research stated that Grounded Theory as a research design produces a theory or framework as an end product. It should represent the lived experiences of the participants.

The following framework of Crisis on Discernment of Vocation (CDV) is a single schema or structure. It consists of three column arrows, and four separate arrows. Underneath it is a big arrow that signals the whole process of CDV from the origin of crises to the way of coping with the crises, places of refuge during crisis, internal dispositions of seminarians and assessment of the crises by the seminarians. This framework aims to understand the experiences of seminarians on CDV while undergoing seminary formation. This will be explained further in the next paragraph.

Figure1. Framework of Crisis on Discernment of Vocation

Explanation of the Framework for Crisis on Discernment of Vocation (CDV).

A. The origin of the crises of seminarians mostly is from the family. Erikson’s (1993) theory of Psychosocial Development speaks of mother and parents as sources of crisis in the initial stages of development. If the child was not able to resolve the psychological crisis of the first two stages it will have a great effect on the succeeding stage. Crises started in the family which might have been going on for an extended time as the seminarians mature. Denzin (2003) calls this crisis as “cumulative epiphany.” Examples of crises that affected the seminarians’ discernment of vocation are health in the family, crisis on relationship, (relationship within the family), and sexual abuse. The sexual, physical and verbal abuses are considered “relived epiphany” according to Denzin (2003).

The family is a very crucial part of the crises of seminarians on their discernment of vocation. Many of the crises of seminarians are “on relationships within the family.” Also, the health and death in the family is a most common crisis that affected the seminarians’ discernment of vocation. This is very revealing of the culture of the participants who are Asians, particularly Filipinos. Tokonaga (2014) stated Eastern culture gives great value to the family. Wherever they are, the Filipinos think of their family. Berk (2018) presented in her book that lifespan development is lifelong. In the development of a person there is something stable, continuous, and dynamic. If seminarians’ crisis started in the family at a young age, then there is a possibility that they bring their crisis from home to the seminary.

Another most common crisis that affected the seminarians’ discernment of vocation is health and death in the family. The death of one of the parents can be a “major epiphany”. In the interview, one seminarian also said that he has difficulty of relating to priest-formator and he attributed this to his difficulty of relating to his father in his developmental years at home. Denzin (2003) categorized this “illuminative epiphany” or “relived epiphany.”

B. In the interview, we have discovered that there are varied beginnings of the vocation of seminarians, which also are to some extent, their greater exposure to the Catholic Church. Of the selected participants, many of them started as convent boys or sacristans. Some reside with the parish priest. Some of them have religious family backgrounds, which mean either father or mother or grandparents are regular mass goers. When these seminarians were young their parents or grandparents used to bring them to the church regularly. And when these seminarians were already old enough to go to church, they joined religious organizations such as youth ministry and choir in the church. It is to be noted that less than half of college and theological seminarians entered the minor seminary. They were too young to decide, but some of their brothers or relatives are already in the minor seminary. So, they were also influenced by these brothers or relatives who were in the minor seminary before they did.

There were also other encouragers or inspirers in the origin of their vocation, either a priest, bishop, parent, seminarian who told them about seminary formation or priesthood that “touched” them. According to many seminarians these encouragers said, “You become a priest ok.” “You enter the seminary.” “Try the minor seminary, it is good there.” These words seemed irresistible to them. There were also revelations in the interview where these selected seminarians were products of “vocation campaigns.” Seminarians dressed in clerical garb, who go to the schools, to parishes and talk to young people narrating their story of how the Lord called them to the priesthood and entered the seminary has an impact on them. These opened the innocent eyes of would-be-seminarians to the realities of seminary life. The desire to enter the seminary came in various forms, and these were during their developmental years. Before their entrance to seminary formation, there were already some companions that guided them in their initial and “little” discernment of vocation.

Williams (2017) based his article on the survey conducted by Center for Applied Research in the Apostolate (CARA). In the year 2017 ordinands, 444 candidates responded to the survey, and 77 percent were altar servers, 51 percent were lectors, 42 percent Extraordinary Ministers of Holy Communion, and 34 percent were youth ministers. There is a consistent correlation between altar boys and the priesthood. There are 80 percent of the ordinands, who belong to homes where parents are Catholic. Seventy-six percent of the ordinands were encouraged in their vocation by a priest (Williams, 2017).

C. How did the seminarians cope up with their crisis in discernment of vocation while undergoing formation? There are three considerations that seminarians reveal in the interview as part of their coping mechanisms with the crises of discernment of vocation namely: What did they do? Where did they go? What was within them?

What did they do when they experienced crises in discernment of vocation? All the seminarians talked to their fellow seminarians. The coping behavior involved reaching out, letting the crisis out, and consulting. Some seminarians choose whom to approach such as classmates only when they confide their crises. Some seminarians picked only those who belong to their diocese (or archdiocese), for they live in one community as part of the seminary structure. Some effeminate seminarians choose only those who are effeminate seminarians (“circle of friends”) when discussing their crises. Some seminarians picked out only their real best friends to converse with about their crisis.

Four seminaries are fortunate to have professional licensed counselors or clinical psychologists, who are part of the team of formators inside the seminary. These professional helpers have regular time with these seminarians. Only one college seminary did not have an official counselor or clinical psychologist. The seminarians who were having a crisis in discernment of vocation have sessions or at least discussed initially their crisis directly or indirectly as part of their coping up.

The office of the bishop is mandated by Canon Law to appoint spiritual directors in the seminary (Canon 239 section 1). This is part of the Catholic Church’s duty to guard, foster, nourish, and love vocation because it is a gift from God (Francis 2016; John Paul II, 1992). Many seminarians go to the spiritual director regularly and discuss their crisis as part of their coping up mechanism. However, some did not go to their spiritual director to discuss their crisis because their understanding of spiritual direction is purely “spiritual matters.” This means that they consider their crisis not spiritual in nature. CS9 said, “I did not talk to him (The Spiritual Director) about this crisis because one time, some sensitive matters came out in my evaluation, and I never discussed these to anyone.” This particular seminarian felt betrayed by the Spiritual Director.

Where did they go? All seminarians experienced going to the chapel on their own as a place of refuge. They prayed when they experienced a crisis on discernment of vocation. Some just sit down inside the oratory of the seminary to recollect themselves, and they feel strengthened and refreshed to go on in their seminary formation amidst the crisis they are going through. Another place where seminarians go is the seminary grounds. The premises of the seminary include the garden, rooftop, under the trees, pathway, basketball court, library, dining hall, and hallways. As they stroll, they discern their crisis which affected their vocation very much. Some get insights, enlightenment, and greater awareness of their situation inside the seminary. These physical environments in the seminary serve as coping mechanisms to get through their crisis on discernment of vocation.

Ackerman (2018) in an article said that support groups are part of healthy coping. Their fellow seminarian is the best person to support them especially that they are in the same situation, same location, and same life orientation. Adubale and Aluede (2017) in their research stated that seminarians go to their spiritual director when there is no counseling service in the seminary. The American Program for Priestly Formation (2006) upholds that the seminarians have give-and-take influence to their fellow seminarians. The Updated Philippine Program for Priestly Formation (2006) advocates that seminarians themselves are agents of formation to their fellow seminarians.

The help extended by the seminary counselor, psychologist, the Spiritual Director, and also the places where the seminarians go as a way of coping with the crisis in discernment of vocation are all external factors. What internal factors helped the seminarians in coping with the crisis in discernment of vocation? In the interview, the seminarians uncovered these dispositions or internal gifts namely:

- Spiritual & psychological maturity

- Determination

- Discerning

- Sacrificing

- Hopeful

- Positive disposition

- Humility

- Openness

- Patience

- Prudence

- Joy

- Grounded on God

- Deep faith in God.

As a sign that they possess these internal dispositions is the reality they are still inside the seminary undergoing seminary formation. These characteristics of seminarians are big factors in the coping mechanisms of the crisis on discernment of vocation.

D. The Assessment of seminarians on their crises that affected their discernment of vocation:

In the interview, we learned that initially, there were negative reactions of seminarians as they experienced crises but later on the bearing of the crises on the seminarians is very constructive. Although in facing their crisis, obscurity and struggle were encountered, and in the end, the crises are valued as something positive. The following are the very words of seminarians themselves.

- It helped me to be more critical and discerning.

- I became more compassionate.

- It strengthened my vocation.

- It strengthened my spirituality because I prayed more.

- Because of this crisis I started to trust people like our counselor in the seminary.

- I learned to communicate expressing my disappointments and opinions.a. with my parents

- It became an opportunity for me to appreciate my vocation.

- I came to terms with myself.

- I started to see hope.

- God has a purpose for me in my encounter with this crisis

- Priesthood is not just for my family but for my bigger family which will be my parish in the future.

- It made me try harder and give my best in seminary formation.

- I came to a greater understanding of myself.

- The crises made me a mature person.

- I became flexible, prudent and resilient.

- I discovered my weakness and strength.

- I became humble, a person who needed help.

- I became a listener.

- I saw positive changes in my personality such as openness to correction and becoming prudent.

Davis (2021) speaks of different stages of crisis, and part of this is the post-crisis and during post-crisis, people are in the condition of learning. Breitbart (2017) writes that meaning-making is a defining characteristic of human beings. For Breitbart (2017), there is meaning and hope even when people suffer.

Conclusions

This research successfully generated a framework that emerged from the lived experiences of crisis on discernment of vocation of seminarians while on formation. There were five crises with sub crises that the seminarians went through. The origin of these crises is their own family. Their own family inspired them to listen to their calling. The family centeredness of Filipino seminarians is something cultural. There are different stages of the seminarians’ crises. There are also coping mechanisms, which include the external help and internal dispositions of seminarians. The way the seminarians assessed their crises is constructive, something necessary for their growth.

This study can help formators, clinicians, and counselors assigned in the seminary in accompanying seminarians undergoing seminary formation. Crisis in discernment of vocation is something that is normal as ordinary people experience “turning points in life.” There is a process that is involved in the crisis in discernment of vocation. There is an origin before the crisis happened. And likewise there are responses and consequences of these crises. The research promotes the presence of professional psychologists, counselors, working together with the Spiritual Directors and priest-formators to help better the journey of seminarians who are in crisis.

With the assistance of professional helpers, seminarians will be able to understand their crisis with the help of this framework on CDV. They will no longer be like a ball inside the pinball machine going to different people without perspective of the crisis that they are facing. With greater perspective on the crisis on discernment of vocation, hopefully, there will be greater retention of matured candidates to the priesthood. Seminarians will understand their crises as something normal that they have to undergo and these are something good for their spiritual and psychological maturity.

References

Ackerman, C. E. (2021, May 30). Coping mechanism: dealing with life’s disappointments in a healthy way. Positive Psychology. https//positivepsychology.com/coping/

Agenzia Fides (2018, October 2). Catholic Church Statistics. https://www.fides.org/en/news/64944-VATICAN_CATHOLIC_CHURCH_STATISTICS_20

Alink A. L., Cyr, C. & Madigan, S. (2019). The effect of maltreatment experiences on maltreating and dysfunctional parenting: A search of mechanism. Development and Psychopathology, 31, 1-7. DOI: 10.1017.S095459418001517

Allen, D.M. (2018). Coping with critical, demanding, and dysfunctional parent. New Harbinger Publications, Inc. Z Library. https://book4you.org/book/5518557/b1de6d

Berk, L. E. (2018). Development through the lifespan. Pearson.

Breitbart, W. (2017). Meaning-centered psychotherapy in the cancer setting: finding meaning and hope in the face of suffering. Oxford University Press.

Bryant, A. (2017). Grounded theory and grounded theorizing: Pragmatism in research practice. Oxford University Press.

Bugnolo, A. (2020, January20). Celibacy is essential to the priesthood of the new covenant. From Rome. https://www.fromrome.info/2020/01/20/celibacy-is-essential-to-the-priesthood-of-the-new-covenant/

Carver, C. & Scheier, M. (2016). Perspective on personality (8th Ed). Pearson Allyn and Beacon

Catholic Bishops’ Conference of the Philippines (2006). Updated Philippine program for priestly formation. Saint Paul Publication.

Caviola, A. & Colford, J. (2018). Crisis intervention: A practical guide. Sage Publication.

Cherry, K. (2020, January 23). Psychological crisis types and causes. Verywellmind. https://www.verywellmind.com/what-is-a-crisis-2795061

Cornelio, J. (2018, March 9). How the Philippines became catholic. Christianity Today. https://christianitytoday.com/history/2018/february/philippines.html

Corriden, J.A. (2019). Introduction to canon law (3rd Ed). Paulist Press. Cruz, O.V. (2012). Want to be a priest?. CBCP Publication.

Daly, P. (2019, July 22). Celibacy advances the priesthood’s culture of compromised truths. National Catholic Reporter. https://www.ncronline.org/news/accountability/priestly-diary/celibacy-advances-priesthoods-culture-compromised-truths

Davie, M., Grass, M., Holmes, S.R., McDowell, J & Noble, T.A. (2016). New dictionary of theology: historical systematic (2rd Edition). Inter-Varsity Press.

Davis, B. (2021, February 25). What are the four stages of crisis?. Mvorganizing. https://www.mvorganizing.org/what-are-the-4-stages-of-crisis/

Denzin, N.K. (2003). Symbolic interactionism and cultural studies: the politics of interpretation. Blackwell.

Dolejsi, B. (2016). Seminary life – Discernment in the seminary. Archdiocese of Seattle. [Audio file] http://seattlevocations.com/blog/discernment-in-seminary

Erikson, E.H. (1993). Childhood and society (2nd Ed.). Norton & Company. Z. Library. https://book4you.org/book/953768/97dc41 (Originally published in 1963).

Erikson, E.H. (1994). Identity: Youth and crisis. Norton & Company Z. Library. https://book4you.org/book/5907234/2bca55 (Originally Published in 1968).

Feist, J., Feist G. &, Roberts, T (2018). Theories of personality (9th Ed). McGraw-Hill Education.

Fernandez, E. (2001). Leaving the priesthood: A close reading of priestly departures. Ateneo De Manila University Press.

Flannery, A. (Ed.) (2014). Second vatican council: New revised edition. Liturgical Press.

Flynn, S.V. & Korcuska, J.S. (2018) Grounded theory research design: An investigation into practice and procedures, Counseling Outcomes Research and Evaluation, DOI: 10.1080/21501378.2017.1403849

Frankl, V. (2006). Man’s search for meaning. Basic Books. Z. Library. https://book4you.org/book/3592958/8b2247

Glatz, C. (2019, March 6). Number of priests declined for first time in decade, vatican says. Crux. https://cruxnow.com/vatican/2019/03/06/number-of-priests-declined-for-first-time-in-decade-vatican-says/

Griffiths, R. J., Barton-Weston, H.M. & Walsh, D.W. (2016). Sports transition as epiphanies. Journal Amateur Sport, 2(2), 29-49. https://doi.org/10.17161/jas.v2i2.5058

Hunter, R. & Ramsey, N. (Eds.) (2005). Dictionary of pastoral care and counseling. Abingdon Press.

Jackson-Cherry, L.R. & Erford, B.T. (2018). Crisis assessment, intervention, and prevention (3rd Ed). Pearson

James, R.K. & Gilliland, B.E. (2017). Crisis intervention strategies (8th Ed). Cengage Learning.

Knapick, J. & Kosturkova, M. (2018). Crises of catholic seminarians. Journal of Interdisciplinary Research Ad Alta, 8(2), 124-130. https://0-eds.s.ebscohost.com.ustlib.ust.edu.ph/eds/detail/detail?vid=1&sid=00ecfed8-c583-44fb-9bfd-a89e4df49623%40redis&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWRzLWxpdmU%3d#AN=134101954&db=asn

Leeming, D. A. (Ed.) (2020). Encyclopaedia of psychology and religion (3rd Ed). Springer. Z Library. https://book4you.org/book/2296859/ce3946

Marshall, T. (2018, May 30). Our sad decline in priestly vocation: Most priests will retire in 2015-2015. Taylor Marshall. https://taylormarshall.com/2018/05/sad-decline-priestly-vocations-priests-will-retire-2015-2025.html

O’ Connor, A., Carpenter, B. & Coughlan, B. (2018). An exploration of key issues in the debate between classic and constructivist grounded theory, The Grounded Theory Review, 17(1), 90-103.

Pope Francis (2016). Ratio fundamentalis institutionis sacerdotalis (RFIS): The gift of priestly vocation. Saint Paul Publication.

Pope John Paul II, (1992). Post Synodal Apostolic Exhortation Pastores Dabo Vobis. Saint Paul Publication.

Psaroudakis, I, Muller, T. & Salvini, A. (Ed.) (2021). Dealing with grounded theory: discussing, learning and practice. Pisa University Press. https://www.pisauniversitypress.it/scheda-ebook/andrea-salvini-irene-psaroudakis-thaddeus-muller/dealing-with-grounded-theory-9788833395258-575900.html

Public Health Nigeria (2020, July 1). Crisis intervention: Strategies, principles and techniques. Public Health Nigeria. https://www.publichealth.com.ng/tag/crisis-intervention/

Tie, C.Y., Birks, M. & Francis, K. (2019). Grounded Theory research: A design framework for novice researcher. SAGE Open Medicine, 7, 1-8. https://doi.org/10.1177/2050312118822927

Tillich, P. (2008) The Courage to be (2nd Ed). Yale University Press. (Original work published in 1952)

Tokonaga, P. (2014, April 10). East vs. west cultural comparison. https://ism.intervarsity.org/resource/east-vs-west-cultural-comparison

United States Conference of Bishops (2006) Program for priestly formation (5th Edition).

Weigel, G. (2019, August, 28). In praise of today’s seminarian. The Catholic World Report. https://www.catholicworldreport.com/2019/08/28/in-praise-of-todays-seminarians/

Fr. Jesus Cirilo Bala, Jr. (Primary author)

The researcher is a Catholic priest, who studied at Mary Help of Christians College Seminary and Immaculate Conception School of Theology. His clerical assignments are the following: 1) Saint Mary’s Seminary, the high school seminary of the Diocese of Laoag (Prefect of Discipline), 2) St. Jude Thaddeus Parish (Parish Priest) 3) Immaculate Conception School of Theology (Director of Spiritual Formation Year) 4) Mary Cause of our Joy College Seminary (Rector). He is finishing his doctorate in Clinical Psychology at the University of Santo Tomas.

Dr. Lucila O Bance (Co-author)

She graduated with a Doctor of Philosophy major in Clinical Psychology at University of Santo Tomas. Since then she has been teaching at UST for 37 years. She is the first Director of Counseling and Career Center of UST. Also, she was the college secretary of the College of Science of UST for twelve years. She was once the President and Vice President of the Psychological Association of the Philippines. She was also the Vice President of Philippine Guidance and Counseling Association. She is a licensed practicing Guidance Counselor and Certified Psychologist.

It is helpful for discernment. Thanks for the collection and interviews.